preface

September 30, 1965

In late 1965 and early 1966, one of the greatest mass killings of the twentieth century was carried out in Indonesia, the slaughter in a few weeks of hundreds of thousands of real or alleged Communists. The massacres set the stage for Suharto’s thirty-two-year dictatorship. Behind them lay events of a few days, still sinister and obscure. On September 30, 1965 a group of middle-ranking army officers, most of them originating from the Diponegoro Division centred in Semarang, and once commanded by Suharto, attempted a coup de force in Jakarta. Claiming that a Council of Generals was planning to seize power from Sukarno, President of the country since independence, they killed six top generals in Jakarta, took Sukarno to an air base outside the capital, and proclaimed a revolutionary council. In Central Java, local garrisons followed suit. Lieutenant-Colonel Untung of Sukarno’s Presidential Guard was nominal leader of the movement, backed by forces from two battalions in the capital; youths from a recently formed militia containing Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) volunteers were entangled as auxiliaries.

The two Army generals who controlled major concentrations of troops in Jakarta—logically prime targets for the strike—were left untouched. The senior was Suharto. In the course of October 1, he quickly gained control of the situation, putting the leaders of the movement to flight and taking over the air base where they had installed Sukarno. The following day, the risings in Central Java were crushed. With the President now in his hands, Suharto proclaimed the Communist Party, which Sukarno had relied on as a counterweight to the Army, the author of the events of September 30. Two weeks later, a nation-wide pogrom was unleashed to exterminate it. The PKI then numbered some three million members—the largest Communist Party in the world outside Russia and China. By the end of the year, nothing was left of it. In March 1966 Sukarno, held under surveillance in the Presidential Palace, was forced to sign a decree giving Suharto executive authority. A year later, this

new left review 3 may jun 2000

5

became the formal basis for Suharto’s assumption of the Presidency, well after he had in practice become the absolute ruler of the country.

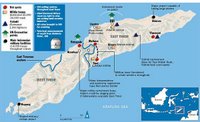

Suharto’s New Order lasted until 1998, when the Asian financial crisis fi nally brought him down. Military terror outlived him in East Timor. But with the election of Wahid as President in 1999, survivors have begun to speak out, breaking the silence that for three decades surrounded the massacres of 1965. But the events that paved the way for the slaughter have yet to be fully explained. Did a Council of Generals ever exist? Who really planned the ‘movement of September 30’, and what were their intentions? Was the PKI, or a section of its leadership, party to the coup? How did Suharto manage to seize power so quickly? The first detailed attempt to consider these problems was a confidential paper by Benedict Anderson and Ruth McVey, written in January 1966, and eventually published by the Cornell Modern Indonesia Project in 1971.1 For this analysis, Benedict Anderson was banned from Indonesia by the military dictatorship for twenty-six years. Last year, able to travel to the country again, he delivered an address in Jakarta in which he urged the need for Indonesians to face the swamp of murder and torture on which the New Order had been built, rather than merely protesting its corruption.2 In the months since, as Wahid has widened the space for political expression, the start of a catharsis has moved more quickly than anyone could have expected. Among the documents to emerge on the genesis of Suharto’s regime, the Defence Speech of Colonel Abdul Latief—leading survivor of the September 30th movement—at his trial in 1979, has been the most pregnant. We publish below Benedict Anderson’s review of it, written in Indonesian for the Jakarta weekly Tempo of 10–16 April of this year.

1 A redaction of some of its findings by Peter Wollen was released in NLR I/36, March–April 1966.2 See ‘Indonesian Nationalism Today and in the Future’, NLR I/235, May–June 1999.

6 nlr 3

benedict anderson

PETRUS DADI RATU

In the early 1930s, Bung Karno [Sukarno] was hauled before a Dutch colonial court on a variety of charges of ‘subversion’. He was perfectly aware that the whole legal process was prearranged by the authorities, and he was in court merely to receive a heavy sentence. Accordingly, rather than wasting his time on defending himself against the charges, he decided to go on the attack by laying bare all aspects of the racist colonial system. Known by its title ‘Indonesia Accuses!’ his defence plea has since become a key historical document for the future of the Indonesian people he loved so well.

Roughly forty-five years later, Colonel Abdul Latief was brought before a special military court—after thirteen years in solitary confi nement, also on a variety of charges of subversion. Since he, too, was perfectly aware that the whole process was prearranged by the authorities, he followed in Bung Karno’s footsteps by turning his defence plea into a biting attack on the New Order, and especially on the cruelty, cunning and despotism of its creator. It is a great pity that this historic document has had to wait twenty-two years to become available to the Indonesian people whom he, also, loves so well.1 But who is, and was, Abdul Latief, who in his youth was called Gus Dul? While still a young boy of fi fteen, he was conscripted by the Dutch for basic military training in the face of an impending mass assault by the forces of Imperial Japan. However, the colonial authorities quickly surrendered, and Gus Dul was briefl y imprisoned by the occupying Japanese.

Subsequently, he joined the Seinendan and the Peta in East Java.2 After the Revolution broke out in 1945, he served continuously on the front lines, at first along the perimeter of Surabaya, and subsequently in Central Java. Towards the end he played a key role in the famous General Assault of March 1, 1949 on Jogjakarta [the revolutionary capital just cap-

new left review 3 may jun 2000

7

tured by the Dutch]: directly under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Suharto. After the transfer of sovereignty in December 1949, Latief led combat units against various rebel forces: the groups of Andi Azis and Kahar Muzakar in South Sulawesi; the separatist Republic of the South Moluccas; the radical Islamic Battalion 426 in Central Java, the Darul Islam in West Java, and finally the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia [CIA-financed and armed rebellion of 1957–58] in West Sumatra. He was a member of the second graduating class of the Staff and Command College (Suharto was a member of the fi rst class). Finally, during the Confrontation with Malaysia, he was assigned the important post of Commander of Brigade 1 in Jakarta, directly under the capital’s Territorial Commander, General Umar Wirahadikusumah. In this capacity he played an important, but not central, role in the September 30th Movement of 1965. From this sketch it is clear that Gus Dul was and is a true-blue combat soldier, with a psychological formation typical of the nationalist freedom-fighters of the Independence Revolution, and an absolute loyalty to its Great Leader.3

His culture? The many references in his defence speech both to the Koran and to the New Testament indicate a characteristic Javanese syncretism. Standard Marxist phraseology is almost wholly absent. And his accusations? The first is that Suharto, then the Commander of the Army’s Strategic Reserve [Kostrad], was fully briefed beforehand, by Latief himself, on the Council of Generals plotting Sukarno’s overthrow, and on the September 30th Movement’s plans for preventive action. General Umar too was informed through the hierarchies of the Jakarta Garrison and the Jakarta Military Police. This means that Suharto deliberately allowed the September 30th Movement to start its operations, and did not report on it to his superiors, General Nasution and General Yani.4 By the same token, Suharto was perfectly positioned to take action against the September 30th Movement, once his rivals at the top of the

1 Kolonel Abdul Latief, Soeharto Terlibat G30S—Pledoi Kol. A. Latief [Suharto was Involved in the September 30 Movement—Defence Speech of Colonel A. Latief ] Institut Studi Arus Informasi: Jakarta 2000, 285 pp. 2 Respectively: paramilitary youth organization and auxiliary military apparatus set up by the Japanese.3 Ironic reference to the title Sukarno gave himself in the early 1960s.4 Nasution was Defence Minister and Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, Yani Army Chief of Staff. Yani was killed on October l, and Nasution just escaped with his life.

8

nlr 3

military command structure had been eliminated. Machiavelli would have applauded.

We know that Suharto gave two contradictory public accounts of his meeting with Latief late in the night of September 30th at the Army Hospital. Neither one is plausible. To the American journalist Arnold Brackman, Suharto said that Latief had come to the hospital to ‘check’ on him (Suharto’s baby son Tommy was being treated for minor burns from scalding soup). But ‘checking’ on him for what? Suharto did not say. To Der Spiegel Suharto later confided that Latief had come to kill him, but lost his nerve because there were too many people around (as if Gus Dul only then realized that hospitals are very busy places!). The degree of Suharto’s commitment to truth can be gauged from the following facts. By October 4, 1965, a team of forensic doctors had given him directly their detailed autopsies on the bodies of the murdered generals. The autopsies showed that all the victims had been gunned down by military weapons. But two days later, a campaign was initiated in the mass media, by then fully under Kostrad control, to the effect that the generals’ eyes had been gouged out, and their genitals cut off, by members of Gerwani [the Communist Party’s women’s affiliate]. These icy lies were planned to create an anti-communist hysteria in all strata of Indonesian society.

Other facts strengthen Latief’s accusation. Almost all the key military participants in the September 30th Movement were, either currently or previously, close subordinates of Suharto: Lieutenant-Colonel Untung, Colonel Latief, and Brigadier-General Supardjo in Jakarta, and Colonel Suherman, Major Usman, and their associates at the Diponegoro Division’s HQ in Semarang. When Untung got married in 1963, Suharto made a special trip to a small Central Javanese village to attend the ceremony. When Suharto’s son Sigit was circumcised, Latief was invited to attend, and when Latief’s son’s turn came, the Suharto family were honoured guests. It is quite plain that these officers, who were not born yesterday, fully believed that Suharto was with them in their endeavour to rescue Sukarno from the conspiracy of the Council of Generals. Such trust is incomprehensible unless Suharto, directly or indirectly, gave his assent to their plans. It is therefore not at all surprising that Latief’s answer to my question, ‘How did you feel on the evening of October 1st?’—Suharto had full control of the capital by late afternoon—was, ‘I felt I had been betrayed.’

anderson: Indonesia

9

Furthermore, Latief’s account explains clearly one of the many mysteries surrounding the September 30th Movement. Why were the two generals who commanded directly all the troops in Jakarta, except for the Presidential Guard—namely Kostrad Commander Suharto and Jakarta Military Territory Commander Umar—not ‘taken care of’ by the September 30th Movement, if its members really intended a coup to overthrow the government, as the Military Prosecutor charged? The reason is that the two men were regarded as friends. A further point is this. We now know that, months before October 1, Ali Murtopo, then Kostrad’s intelligence chief, was pursuing a foreign policy kept secret from both Sukarno and Yani. Exploiting the contacts of former rebels,5 clandestine connexions were made with the leaderships of two then enemy countries, Malaysia and Singapore, as well as with the United States. At that time Benny Murdani6 was furthering these connexions from Bangkok, where he was disguised as an employee in the local Garuda [Indonesian National Airline] office. Hence it looks as if Latief is right when he states that Suharto was two-faced, or, perhaps better put, two-fisted. In one fist he held Latief–Untung–Supardjo, and in the other Murtopo–Yoga Sugama7–Murdani.

The second accusation reverses the charges of the Military Prosecutor that the September 30th Movement intended to overthrow the government and that the Council of Generals was a pack of lies. Latief’s conclusion is that it was precisely Suharto who planned and executed the overthrow of Sukarno; and that a Council of Generals did exist —composed not of Nasution, Yani, et al., but rather of Suharto and his trusted associates, who went on to create a dictatorship based on the Army which lasted for decades thereafter. Here once again, the facts are on Latief’s side. General Pranoto Reksosamudro, appointed by President/Commander-in-Chief Sukarno as acting Army Commander after Yani’s murder, found his appointment rejected by Suharto, and his person soon put under detention. Aidit, Lukman and Nyoto, the three top leaders of the Indonesian Communist Party, then holding ministerial rank in Sukarno’s government, were murdered out of hand. And although President Sukarno did his utmost to prevent it, Suharto and

5 From the 1957–58 civil war, when these people were closely tied to the CIA as well as the Special Branch in Singapore and Malaya.6 The legendary Indonesian military intelligence czar of the 1970s and 1980s. 7 A Japanese-trained high-ranking intelligence offi cer.

10 nlr 3

his associates planned and carried out vast massacres in the months of October, November and December 1965. As Latief himself underlines, in March 1966 a ‘silent coup’ took place: military units surrounded the building where a plenary cabinet meeting was taking place, and hours later the President was forced, more or less at gunpoint, to sign the super-murky Supersemar.8 Suharto immediately cashiered Sukarno’s cabinet and arrested fifteen ministers. Latief’s simple verdict is that it was not the September 30th Movement which was guilty of grave and planned insubordination against the President, ending in his overthrow, but rather the man whom young wags have been calling Mr. TEK.9

Latief’s third accusation is broader than the others and just as grave. He accuses the New Order authorities of extraordinary, and wholly extralegal, cruelty. That the Accuser is today still alive, with his wits intact, and his heart full of fire, shows him to be a man of almost miraculous fortitude. During his arrest on October 11, 1965, many key nerves in his right thigh were severed by a bayonet, while his left knee was completely shattered by bullets (in fact, he put up no resistance). In the Military Hospital his entire body was put into a gypsum cast, so that he could only move his head. Yet in this condition, he was still interrogated before being thrust into a tiny, dank and filthy isolation cell where he remained for the following thirteen years. His wounds became gangrenous and emitted the foul smell of carrion. When on one occasion the cast was removed for inspection, hundreds of maggots came crawling out. At the sight, one of the jailers had to run outside to vomit. For two and a half years Latief lay there in his cast before being operated on. He was forcibly given an injection of penicillin, though he told his guards he was violently allergic to it, with the result that he fainted and almost died. Over the years he suffered from haemorrhoids, a hernia, kidney stones, and calcification of the spine. The treatment received by other prisoners, especially the many military men among them, was not very different, and their food was scarce and often rotting. It is no surprise,

8 Acronym for Surat Perintah Sebelas Maret, Decree of March 11, which turned over most executive functions ad interim to Suharto; the acronym deliberately exploits the name of Semar, magically powerful figure in Javanese shadow puppet theatre.

9 ‘Thug Escaped from Kemusu’: the Suharto regime regularly named all its supposed subversive enemies as GPK, Gerakan Pengacau Keamanan, or Order-Disturbing Elements. The wags made this Gali Pelarian Kemusu—Suharto was born in the village of Kemusu.

anderson: Indonesia 11

therefore, that many died in the Salemba Prison, many became paralytics after torture, and still others went mad. In the face of such sadism, perhaps even the Kempeitai10 would have blanched. And this was merely Salemba—one among the countless prisons in Jakarta and throughout the archipelago, where hundreds of thousands of human beings were held for years without trial. Who was responsible for the construction of this tropical Gulag?

History textbooks for Indonesia’s schoolchildren speak of a colonial monster named Captain ‘Turk’ Westerling. They usually give the number of his victims in South Sulawesi in 1946 as forty thousand. It is certain that many more were wounded, many houses were burned down, much property looted and, here and there, women raped. The defence speech of Gus Dul asks the reader to reflect on an ice-cold ‘native’ monster, whose sadism far outstripped that of the infamous Captain. In the massacres of 1965–66, a minimum of six hundred thousand were murdered. If the reported deathbed confession of Sarwo Edhie to Mas Permadi is true, the number may have reached over two million.

11 Between 1977 and 1979, at least two hundred thousand human beings in East Timor died before their time, either killed directly or condemned to planned death through systematic starvation and its accompanying diseases. Amnesty International reckons that seven thousand people were extra-judicially assassinated in the Petrus Affair of 1983.

12 To these victims, we must add those in Aceh, Irian, Lampung, Tanjung Priok and elsewhere. At the most conservative estimate: eight hundred thousand lives, or twenty times the ‘score’ of Westerling. And all these victims, at the time they died, were regarded officially as fellow-nationals of the monster.

Latief speaks of other portions of the national tragedy which are also food for thought. For example, the hundreds of thousands of people who spent years in prison, without clear charges against them, and without any due process of law, besides suffering, on a routine basis, excruciat

10 Japanese military police, famous for war-time brutality.11 Then Colonel Sarwo Edhie, commander of the elite Red Beret paratroops, was the operational executor of the massacres; Mas Permadi is a well-known psychic.12 The organized slaughter of petty hoodlums, often previously agents of the regime. A grim joke of the time called the death-squads of soldiers-in-mufti ‘Petrus’, as in St. Peter, an acronym derived from Penembak Misterius or Mysterious Killers.

12 nlr 3

ing torture. To say nothing of uncountable losses of property to theft and looting, casual, everyday rapes, and social ostracism for years, not only for former prisoners themselves, but for their wives and widows, children, and kinfolk in the widest sense. Latief’s J’accuse was written twenty-two years ago, and many things have happened in his country in the meantime. But it is only now perhaps that it can acquire its greatest importance, if it serves to prick the conscience of the Indonesian people, especially the young. To make a big fuss about the corruption of Suharto and his family, as though his criminality were of the same gravity as Eddy Tansil’s,13 is like making a big fuss about Idi Amin’s mistresses, Slobodan Miloševic´’s peculations, or Adolf Hitler’s kitschy taste in art. That Jakarta’s middle class, and a substantial part of its intelligentsia, still busy themselves with the cash stolen by ‘Father Harto’ (perhaps in their dreams they think of it as ‘our cash’) shows very clearly that they are still unprepared to face the totality of Indonesia’s modern history. This attitude, which is that of the ostrich that plunges its head into the desert sands, is very dangerous. A wise man once said: Those who forget/ignore the past are condemned to repeat it. Terrifying, no?

Important as it is, Latief’s defence, composed under exceptional conditions, cannot lift the veil which still shrouds many aspects of the September 30th Movement and its aftermath. Among so many questions, one could raise at least these. Why was Latief himself not executed, when Untung, Supardjo, Air Force Major Suyono, and others had their death sentences carried out? Why were Yani and the other generals killed at all, when the original plan was to bring them, as a group, face-to-face with Sukarno? Why did First Lieutenant Dul Arief of the Presidential Guard, who actually led the attacks on the generals’ homes, subsequently vanish without a trace? How and why did all of Central Java fall into the hands of supporters of the September 30th Movement for a day and a half, while nothing similar occurred in any other province? Why did Colonel Suherman, Major Usman and their associates in Semarang also disappear without a trace? Who really was Syam alias Kamaruzzaman14—former official of the Recomba of the Federal

13 Famous high-flying Sino-Indonesian crook who escaped abroad with millions of embezzled dollars.14 Allegedly the head of the Communist Party’s secret Special Bureau for military affairs, and planner of the September 30th Movement.

anderson: Indonesia 13

State of Pasundan,15 former member of the anti-communist Indonesian Socialist Party, former intelligence operative for the Greater Jakarta Military Command at the time of the huge smuggling racket run by General Nasution and General Ibnu Sutowo out of Tanjung Priok, as well as former close friend of D. N. Aidit? Was he an army spy in the ranks of the Communists? Or a Communist spy inside the military? Or a spy for a third party? Or all three simultaneously? Was he really executed, or does he live comfortably abroad with a new name and a fat wallet?

Latief also cannot give us answers to questions about key aspects of the activities of the September 30th Movement, above all its political stupidities. Lieutenant-Colonel Untung’s radio announcement that starting from October 1st, the highest military rank would be the one he himself held, automatically made enemies of all the generals and colonels in Indonesia, many of whom held command of important combat units. Crazy, surely? Why was the announced list of the members of the so-called Revolutionary Council so confused and implausible?16 Why did the Movement not announce that it was acting on the orders of President Sukarno (even if this was untrue), but instead dismissed Sukarno’s own cabinet? Why did it not appeal to the masses to crowd into the streets to help safeguard the nation’s head? It passes belief that such experienced and intelligent leaders as Aidit, Nyoto and Sudisman17 would have made such a string of political blunders. Hence the suspicion naturally arises that this string was deliberately arranged to ensure the Movement’s failure. Announcements of the kind mentioned above merely confused the public, paralysed the masses, and provided easy pretexts for smashing the September 30th Movement itself. In this event, who really set up these bizarre announcements and arranged for their broadcast over national radio?

15 In 1948–49, the Dutch set up a series of puppet regimes in various provinces they controlled to offset the power and prestige of the independent Republic. Recomba was the name of this type of regime in Java, and Pasundan is the old name for the Sundanese-speaking territory of West Java. 16 The Movement proclaimed this Council as the temporary ruling authority in Indonesia, but its membership included right-wing generals, second-tier leftwingers, and various notoriously opportunist politicians, while omitting almost all figures with national reputations and large organizations behind them. 17 Secretary-General of the Communist Party.

14 nlr 3

Most of the main actors in, and key witnesses to, the crisis of 1965, have either died or been killed. Those who are still alive have kept their lips tightly sealed, for various motives: for example, Umar Wirahadikusumah, Omar Dhani, Sudharmono, Rewang, M. Panggabean, Benny Murdani, Mrs. Hartini, Mursyid, Yoga Sugama, Andi Yusuf and Kemal Idris.18 Now that thirty-five years have passed since 1965, would it not be a good thing for the future of the Indonesian nation if these people were required to provide the most detailed accounts of what they did and witnessed, before they go to meet their Maker?

According to an old popular saying, the mills of God grind slowly but very fi ne. The meaning of this adage is that in the end the rice of truth will be separated from the chaff of confusion and lies. In every part of the world, one day or another, long-held classified documents, memoirs in manuscript locked away in cabinets, and diaries gathering dust in the attics of grandchildren will be brought to His mill, and their contents will become known to later generations. With this book of his, ‘shut away’ during twenty-one years of extraordinary suffering, Abdul Latief, with his astonishing strength, has provided an impressive exemplification of the old saying. Who knows, some day his accusations may provide valuable material for the script of that play in the repertoire of the National History Shadow-Theatre which is entitled . . . well, what else could it be?—Petrus Becomes King.

In traditional Javanese shadow-theatre, Petruk Dadi Ratu is a rollicking farce in which Petruk, a well-loved clown, briefly becomes King, with predictably hilarious and grotesque consequences. For Petrus, read Killer—see note 12 above. Suharto notoriously saw himself as a new kind of Javanese monarch, thinly disguised as a President of the Republic of Indonesia.

18 Omar Dhani: Air Force chief in 1965, sentenced to death, had his sentence reduced to life imprisonment, and was recently released. Sudharmono: for decades close aide to Suharto. Rewang: former candidate member of the Communist Party’s Politbureau. Panggabean: top general in Suharto’s clique and his successor as commander of Kostrad. Hartini: Sukarno’s second wife in 1965. Mursyid: Sukarnoist general heading military operations for the Army Staff in 1965, subsequently arrested. Yusuf and Idris: both these generals played central roles in the overthrow of Sukarno.

anderson: Indonesia 15

The day of self-determination,

August 30, 1999

The day of self-determination,

August 30, 1999

The Independence Day,

May 20, 2002.

The Independence Day,

May 20, 2002.

Aceh, PHIA Poster,

Langsa, Eastern Aceh.

Aceh, PHIA Poster,

Langsa, Eastern Aceh.

Mahdi's Aceh in Distress,

Banda Aceh, Oct, 2005.

Mahdi's Aceh in Distress,

Banda Aceh, Oct, 2005.

General Elections,

Apr, 2004, Aceh

General Elections,

Apr, 2004, Aceh

General Elections,

Apr, 2004, Tiro, Pidie, Aceh

General Elections,

Apr, 2004, Tiro, Pidie, Aceh

General Elections,

Apr, 2004, Sawang, Aceh.

Aceh at war, DM, Darurat Militer, 2003-04

General Elections,

Apr, 2004, Sawang, Aceh.

Aceh at war, DM, Darurat Militer, 2003-04

Tsunami, Sadness.

Tsunami, Sadness.

Tsunami, A South Korean NGO,

Meulaboh, Jan. 2005

Tsunami, A South Korean NGO,

Meulaboh, Jan. 2005

Tsunami, Ulee Lheue,

Aceh, Feb. 2005.

Tsunami, Ulee Lheue,

Aceh, Feb. 2005.

Juha Christensen,

Helsinki, Apr, 2005.

Juha Christensen,

Helsinki, Apr, 2005.

M.Ahtisaari, CMI,

Helsinki, Jan-August, 2005.

M.Ahtisaari, CMI,

Helsinki, Jan-August, 2005.

Helsinki, August 2005

Helsinki, August 2005

Peace Talks,

Helsinki Jan-August 2005

Peace Talks,

Helsinki Jan-August 2005

The Signing Ceremony,

Helsinki, August. 15, 2005

The Signing Ceremony,

Helsinki, August. 15, 2005

Ready for de-commisioning,

Central Aceh, Sept. 2005.

Ready for de-commisioning,

Central Aceh, Sept. 2005.

Peace = Anti Militarism

Peace = Anti Militarism